By Aileen Brenner Houston

How can the writing center help military students communicate successfully with their polarizing audiences: military and academia?

Exploring how writing can bridge the gap between military students’ discourse communities.

The struggle of the student writer is not the struggle to bring out that which is within; it is the struggle to carry out those ritual activities that grant our entrance into a closed society.

— David Bartholomae

It’s 07:55 on a Tuesday. Uniform day. Your black leather shoulder bag—carried by hand today, no danger of the strap displacing your carefully positioned medals and ribbons—still smells of cinnamon and blueberries, remnants of your daughter’s oatmeal flecked unceremoniously in the bag’s lining. You’d scooped out most of the gloopy mess with a paper towel on your drive to campus (you had planned to bike, to keep up with PT, but you were running late after the breakfast incident), but you can see the first printed-out page of your literature review peeking from between your books, and it’s earmarked with drying milk and oats.

You whisk into the library through the Starbucks entrance. It’s 07:56. Your writing center appointment is at 08:00. You’d been lucky to snag the first appointment of the day—enough time to regroup before your 10:00 class—but now you have a choice to make: print a fresh copy of your paper to avoid sticky cinnamon stains on your dress uniform sleeve, or risk a dry-cleaning run in favor espresso, the sumptuous Starbucks aroma tempting you to the counter.

You are a student at the Naval Postgraduate School trying to mesh your military life with your academic life, and you will need an alarming amount of coffee to get through this day.

Military and Academia at the Graduate Writing Center

Five and a half years ago, I showed up, at 07:55 on a Tuesday, for my first day as a full-time writing coach at the Naval Postgraduate School’s Graduate Writing Center. Unlike many collegiate writing centers, which are staffed by part-time student tutors, the writing center at NPS has a full-time staff of professional academic coaches and instructors. It was my dream job, though it came with a degree of unease. As a relatively new military spouse but a long-time writing tutor and editor, I was more comfortable among the library’s musty book stacks and old-coffee-bean aroma than I was in the sea of ironclad military officers with carefully combed high-and-tights.

It didn’t take long, however, for me to discover that the students were much more uncomfortable with writing than I was with being called ma’am.

My students and I were on polar ends of a contact zone—language expert Mary Louise Pratt’s term, introduced in my previous post, for a place where cultures meet and clash, particularly when it comes to language and writing norms.

Back when I started, the writing center at NPS was still new: a fledgling response to the Navy Inspector General’s call for improved research and writing at its graduate educational institution. Though NPS was established in 1909, it wasn’t until 2012 that the Navy Inspector General commented on how the disconnect between its two discourse communities, military and academia, was manifesting unfavorably in student writing.

The Graduate Writing Center came to be shortly thereafter, and has grown into a mighty force. On my first day at the writing center, I was one of only six writing coaches; today there are fourteen coaches who offer one-to-one sessions along with a robust schedule of teaching, presentations, and resource creation.

What hasn’t changed in that time, however, is the culture clash between military and academia, and our job at the writing center to negotiate those two worlds so that our students can effectively communicate with, and perhaps harmonize, these polarizing discourse communities.

Brass versus (8 a.m.) Class

Discourses, for me, crucially involve … characteristic ways of acting-interacting-feeling-emoting-valuing-gesturing-posturing-dressing-thinking-believing-knowing-speaking-listening (and, in some Discourses, reading-and-writing, as well).

—James Gee (38)

While military students are writing for familiar faces in the national security world, they’re writing for new ones as well: academics. It is government officials and policymakers—some of whom are academics, some military—who come together to review our military’s national security options, including the student writing that departs military institutions such as the Naval Postgraduate School.

James E. Porter, a prolific author of books on professional communication and rhetoric, defines a discourse community as “a group of individuals bound by a common interest who communicate through approved channels…. Each forum has a distinct history and rules governing appropriateness to which members are obliged to adhere” (228). At military schools, the academic and military discourse communities collide, creating a contact zone of official channels, recognized rules, customs, and communication norms. The students must simultaneously negotiate both sets of norms: they must strive for continued success in their ongoing military careers, which now depend on their academic success.

The difficulty comes in when the norms of these communities, at their core, clash. Howard Wiarda, a former professor at the Naval War College, explains that while the military prioritizes unquestioned order and discipline, academia leans toward skepticism and irreverence (107). And the different “social identities,” as James Gee calls them, that are created around such different disciplines “may seriously conflict with one another” (16). Where the military is bureaucratized and hierarchical—its structure defined legally and its members’ commitment defended to the death (Jordan and Taylor 130)—academic thought requires students to challenge hierarchical notions and forge their own path.

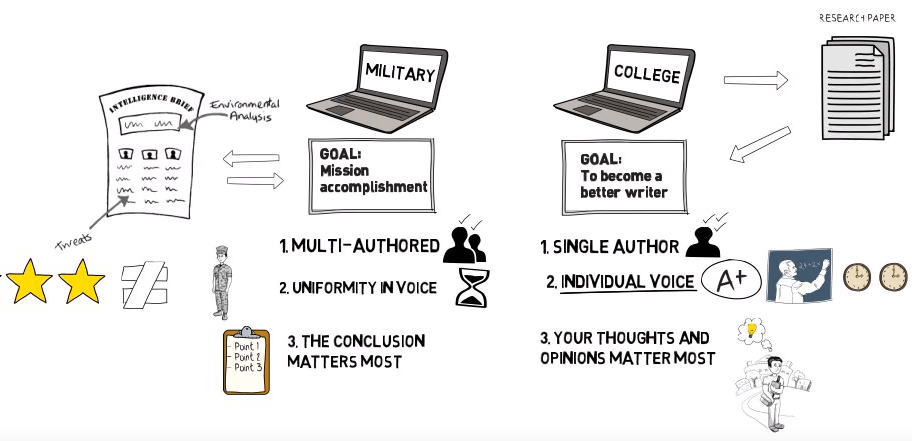

The clash of clans between the academic and military discourse communities includes a clash in writing norms and conventions. Below, for example, is one educator’s take on the major differences between writing for the military and writing for college (in the comments for this blog post below, I invite you to weigh in on these assertions).

At a military college, however, we must respect the approaches of both discourse communities. Gee believes that students are capable of filling simultaneous roles in disparate discourse communities, but admits that “they may face very real conflicts in terms of values and identity” (17). Our job at the writing center is to ease the conflict—to help students translate their military and government experience into academic logic so that they might communicate in and among their discourse communities. It helps, as mentioned in my previous post, to create narratives with them that embrace their new academic identities, build confidence, and connect their worlds.

Harmonizing the Contact Zone

Not So Different?

Despite their fundamental differences, the military and academia have much in common, particularly, if counterintuitively, when it comes to writing conventions.

In 1973, Amos Jordan, a retired brigadier general and professor at the United States Military Academy, and Lieutenant Colonel William Taylor, Jr., also a professor at the Military Academy, recognized a need to reform the military officer education system. In doing so, they highlighted where the military and the academy collide: “The military has many of the same characteristics as the other professions; namely, a specialized body of knowledge acquired through advanced training and experience, a mutually defined and sustained set of standards, and a sense of group identity and corporateness” (130, citing Janowitz).

With these foundational similarities in mind, Desirae Giesman, an editor for Military Review, points to some hallmarks and underappreciated purposes of effective writing for military leaders. Perhaps surprisingly, many are hallmarks of effective academic writing as well:

- active voice

- clarity

- error-free, standard English sentences

- a style that “account[s] for the effective thinking and reasoning that must underlie effective explanations”

- a goal to “help writers become skilled thinkers and communicators … to enhance their critical and creative thinking” (107)

When it comes to writing, the military and academic communities also have just that in common: community. Writing is often seen as a solitary task. How often do you walk through silent study halls and libraries to find tortured seniors holed away in a lonely carrel, invisible yet menacing do-not-disturb signs strung across their laptops as they type?

As described by Porter, however, the concept of intertextuality—the idea that all texts relate to and rely on other texts—reminds us that writing is not an individual act; it is a social one. This is true, regardless of preconceived notions, both in the military and the academy.

When we ask students to write, we are not asking them to invent the wheel; we’re asking them to join conversations about an existing wheel—to be part of larger efforts to make the wheel more effective, or to build solutions based on its design and uses. This is the idea behind intertextuality, but it is also the foundation of academic thought…and of military thought.

Academic papers typically review the literature that has come before them to show the historical importance of and debate surrounding the concepts. National and global security, too, are not new concepts; they predate the academy, even. Our students’ job is to use intertextuality—to study and join the conversations, past and present, of academics and of government partners—to understand where we have been, where we are, and what we should do to get to where we want to be.

Publish or Perish

The saying “publish or perish” is a famous warning among academics, pointing to the importance of continued research and writing for the professoriate. At many institutions, faculty are expected, or required, to publish research as a condition of tenure. Associate Professor Christopher Schaberg, writing for The Chronicle of Higher Education, argues that publishing fuels teaching for professors, and offers an important way for them to communicate.

Publishing is a priority for the U.S. government, too. In its most recent strategic plan, the Government Publishing Office makes it a specific goal to “[increase] the amount of U.S. Government information available for free to the public” (6). This goes back, according to the GPO, to the government’s constitutional obligation to keep citizens informed of its proceedings—specifically through publishing (3). Indeed, in his Guide to Effective Military Writing, William McIntosh calls to this obligation, claiming that “The armed services, like other branches of government, appear almost obsessed with writing” (3).

This shared emphasis on writing and publishing can teach military and academia “how to speak to each other” (Ruszkiewicz 9).

In the publication process particularly, these seemingly at-odds discourse communities collide: the research and writing process involves the skepticism and logic of academia, while the citations, formatting, and editing in the publication process emphasize the order and discipline of the military. During the thesis publishing process at NPS, for instance, we take special care to explain the “logic and good sense” (Wiarda 107) behind citation and grammar norms, working to help each document speak to an academic audience that applauds perfection. As military officers, our students are not strangers to the pursuit of perfection, nor to the pursuit of being heard through a crowd.

Publishing goes beyond giving our students membership into the academic discourse community. It also calls to the social foundations of both the military and academic communities, and merges them to form a unique community of its own.

A New Discourse

Discourses have no discrete boundaries because people are always, in history, creating new Discourses, changing old ones, and contesting and pushing the boundaries of Discourses.

—Gee (21)

Through language and writing, we engage in our social identities and our communities’ conversations; through language and writing, however, we also create our social identities and our communities’ conversations. This is the magic of language, according to Gee (11).

By recognizing the overlapping conventions in military and academia, and by understanding the social languages of these discourse communities, our students have a unique opportunity to join a new, blended discourse community. One that uses academic thought to enhance national security, and that uses their military prowess to advance research.

We must remember not to treat military students as empty vessels that need to be filled and molded. Instead, we must treat them as what they are: minds filled with valuable knowledge and experience, which we can help them expand and translate into academic thought for the shared benefit of their discourse communities.

At the writing center, particularly, we must also remember that our students are service members and public servants. They are budding academics, yes, but they are also cultivating demanding careers for which work-life balance is a known struggle. A service member’s social identity is deeply informed by home and family life, as it is by . We must leave space for our students’ “new Discourses” to be informed by study and service, but also by the sticky cinnamon stains from their daughter’s drying oatmeal.

Works Cited

Bartholomae, David. “Writing Assignments: Where Writing Begins.” Forum: Essays on Theory and Practicing in the Teaching of Writing, edited by Patricia L. Stock, Boynton/Cook, 1983.

Gee, James. Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. Routledge, 1999.

Giesman, Desirae. “Effective Writing for Army Leaders: The Army Writing Standard Redefined.” Military Review, Sept.-Oct. 2015, pp. 106–18, www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20151031_art016.pdf.

GPO FY18-22 Strategic Plan. U.S. Government Publishing Office, www.gpo.gov/docs/default-source/mission-vision-and-goals-pdfs/gpo-strategic-plan-fy2019-2017.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan. 2020.

Jordan, Amos A., and William J. Taylor Jr. “The Military Man in Academia.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political Science, vol. 406, Mar. 1973, pp. 129–45.

McIntosh, William A. Guide to effective Military Writing. 3rd ed., Stackpole Books, 2003.

Porter, James E. “Intertextuality and the Discourse Community.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 5, no. 1, 1986, pp. 34–47.

Pratt, Mary Louise. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession, 1991, pp. 33–40.

Ruszkiewicz, John J. “Writing ‘in’ and ‘across’ the Disciplines: The Historical Background.” Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of English, 19–24 Nov. 1982, Washington, DC, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED224024.pdf.

Schaberg, Christopher. “Publish or Perish? Yes. Embrace It.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 15 Feb. 2016, www.chronicle.com/article/Publish-or-Perish-Yes/235319.

Wiarda, Howard J. Military Brass vs. Civilian Academics at the National War College: A Clash of Cultures. Lexington Books, 2011, ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.nau.edu/lib/nau-ebooks/detail.action?docID=716051.

The views expressed on this website are the author’s alone. They do not reflect the views of the Naval Postgraduate School.

Hi Aileen,

I found your blog post to be so interesting to me as I had never really considered the difference in discourses between military students and non. I enjoyed how you began with a narrative example of a day night look like for a student in this community as they prepare themselves to work in the composition setting. I think you have some great information and examples to help readers understand discourse communities and specifically the difficulties some students may face switching between. Great work!

LikeLike

Hi Aileen,

I really like and agree with the David Bartholomae quote you started your post with. It can be so hard to figure out where you fit in, in academia. It can also be difficult to learn how to properly navigate the different academic Discourse Communities. When I first went to get my BS, I was so nervous about being able to write something worthy of a University. Then, I felt the same way when I began my MA program. I eventually calmed down, got out of my own head, and figured it out. That being said, it can be difficult to truly become comfortable and confident within a Discourse Community. Furthermore, I completely agree with you that military students have a great deal of knowledge to impart. They are not, as you mentioned some people might view them as, “empty vessels.” They have a lot to share, they just need help transforming it into acceptable academic language.

LikeLike

Hi Aileen!

Your blog immediately drew me into the story of a military student. I really enjoyed how you began with a narrative style before delving into some more specific aspects of the military style of writing vs academia. Additionally, your methods of weaving theory and research throughout your blog post made the read quite stimulating. As a response to your ‘clash of clans’ assertion, I find myself agreeing with you to some extent. In my own experience in academia, I would say that collaboration is the norm (graduate school) and is becoming the norm among undergraduate classes, especially in STEM and the arts. It is now less common to have papers be ‘one voice’ and individualistic, and it seems as if academia, in my experience, has begun adapting to the more military style as you put it.

However, the multifaceted identities that these students must have, just with writing, rings true. It must be so much to juggle and switch; almost like a second language.

I also wonder about their experiences in high school, and how this affects their performance as academics. I think that incorporating thoughts on other types of writing or discourse that make up a student at your center would serve to deepen your thoughts in this blog. Additionally, the story in the beginning was so vivid and entertaining that I think your blog may benefit from references to the story, or weaving the continuation throughout your writing (such as ending with mentioning the cinnamon or large amounts of coffee again).

LikeLike

Hi Aileen,

I always enjoy reading anything you write—-whether narrative or argumentative, because your voice is so inviting and brings the reader into your world. I like the structure of this blog post because you provide relevant context and walk the reader through the issues of graduate writing at the college. Your choice of images, using cartoons, kept the mood light.

The only suggestion I have is to maybe add a quote or two about what some of the military writers have said during your tutoring sessions. It would help to further contextualize the environment and challenges you face at the writing center. Are they resistant to searching for their own voice—meaning do they always prefer citing other people instead? Do they have a fear of being wrong or having a minority opinion? My brother was marine and I remember his hyperfocus on making sure what he was doing was right. Also, do you believe that because your spouse is military that your tutees have more respect for your advice? I think that it is pretty awesome you’ve chosen to work alongside your spouse, but as a mentor 🙂

-Amy

LikeLike

Hi Aileen,

I really enjoyed reading your blog! I agree that your writing is fluid and inviting and your opening narrative drew me. You’ve done a great job organizing your content and blog format. Your images are fun and helps keep the flow of your content. Your topic is interesting and you’ve done a great job explaining the clash between two discourse communities. Your point about not reinventing the wheel but joining conversation really stuck with me. Great work!

LikeLike

Aileen,

What an interesting job you have! Interesting that the NPS was founded in 1909 but really didn’t get the needed boost until 2012 when the disconnect became disturbing to the Navy Inspector General, it seems that for over one hundred years student writing was in need of some help that they were not getting. The Graduate Writing Center to the rescue; it sounds like a rewarding job with one-on-one sessions, presentations, resource creation and of course teaching. I was surprised to learn from your blog that there is a clash between military and academia, but then I know nothing about the military, so how would I know without reading your blog. Anyway, hurrah for you to help your students negotiate the two discourse communities so they can communicate and synchronize their writing to obey the rules of the military and the academic world.

It seems effective writing in all areas meet the same qualities:

• clarity

• active voice

• error-free grammar

• consistent style

So, thank you for your interesting blog, I learned so much about the military and I fully enjoyed your section on “publish or perish,” there is a lot of truth in that section.

Judye Houle

LikeLike