By Aileen Brenner Houston

How is academic writing integrally informed by subject matter?

Helping students translate their military subject matter into scholarly genres to address their audience more successfully.

Since the genre constructs the situation, students will not be able to respond appropriately to assigned situations unless they know the appropriate genre.

Amy J. Devitt (583)

In December 2015, my colleagues and I in the thesis office at the Naval Postgraduate School began running preliminary student thesis drafts through Turnitin (later iThenticate), a plagiarism detection software. I had been working for NPS’s writing center and thesis office for a year and some change, and noticed that students were struggling with attribution. However, they weren’t necessarily aware of the struggle, and of the (predominantly unintentional) concerns that were popping up in their papers. We wanted to ensure that our publicly published theses and dissertations could hold up to scrutinizing academy and media eyes—a concern that proved apt in the following years as public plagiarism cases abounded.

There was one big problem, however, with our noble cause to keep our students’ academic integrity squeaky clean:

subject matter expertise

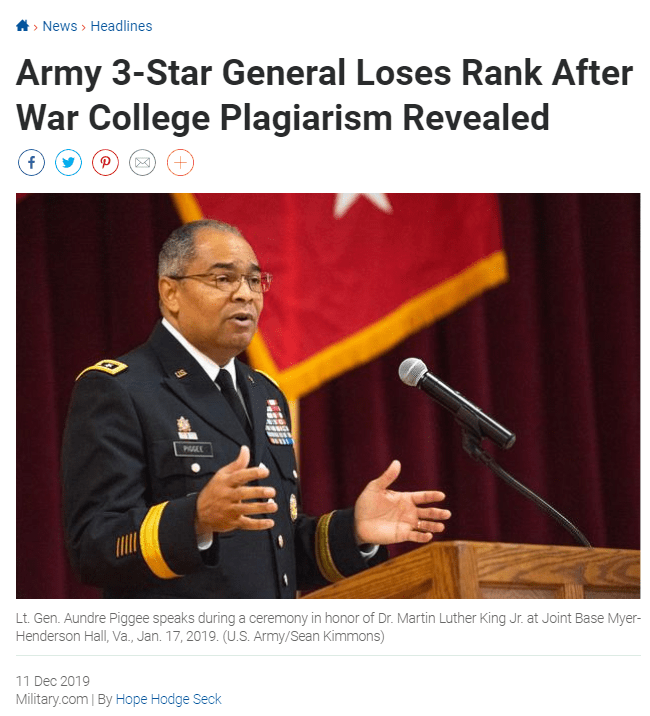

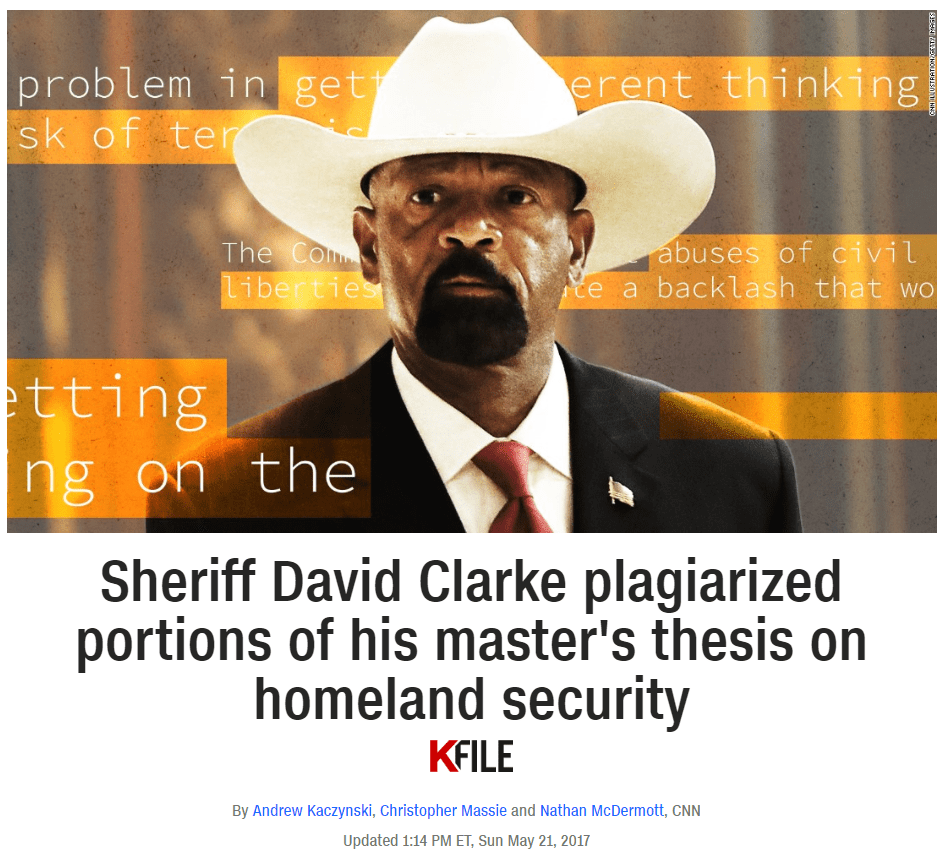

Analyzing a similarity report from a plagiarism detection software is not as straightforward as it seems (and plagiarism itself is not a straightforward subject, as evidenced from The Hill’s counterargument to CNN’s accusations about Sherriff Clarke, and much debate among academics).

Among the complications of analyzing plagiarism reports are the two shown below, which can go hand-in-hand: false positives and common language.

For information on how the Naval Postgraduate School uses iThenticate, read about the Graduate Writing Center’s approach, and see our iThenticate FAQ.

The writing center coaches who were tasked with analyzing the reports, myself among them, found themselves struggling to distinguish between problematic text matches and common language in our students’ fields.

As coaches, we pride ourselves in our ability to help students with their writing, even if we understand the subject matter superficially. When we got into the weeds of academic writing in this context, however, we had to rely on our students to fill in the knowledge gaps.

This was an important reminder for us at the writing center: though our students are writing in a genre that we know well, their subject matter is an integral ingredient that informs, and indeed helps create, that genre.

Defining Genre

When we think of genres in writing, we tend to think of big categories that define the types of reading we do: fiction and nonfiction; mystery stories and news articles; technical reports and scientific studies; even social media.

And our students are navigating a wealth of genres in their daily life at a military school: government directives and instructions; journal articles and lab reports; command orders and counseling statements; literature reviews and historical analyses.

While genre has been traditionally defined as a system for classifying “types of texts according to their forms,” rhetoric and composition scholar Amy J. Devitt argues that genre is not defined by form alone but rather by form plus content (574). Rather than classifying our reading experiences into distinct categories based on “formal features” (575), she suggests we allow content and social situations to guide meaning-making in our writing.

In this conception, genre allows room for blurred boundaries and evolution. Just as our students must blend their military identities with their academic identities, they must blend their growing military expertise with their new academic expertise. In doing so, they create a blended genre that allows these communities to speak to each other.

Blurred Lines: Genre, Subject Matter, and Meaning-Making

What we often diagnose as ignorance of a situation or inability [for students] to imagine themselves in another situation may in fact be ignorance of a genre or inability to write a genre they have not sufficiently read: they may feel great love but be unable to write a love sonnet.

Devitt (583)

Though Devitt encourages us to resist the rigidity of classification systems, she reminds us, too, not to “discard the significance of form in genre” (575, citing Coe).

Our student writers may be best positioned to communicate with their communities given an understanding of the form of writing for academia, and how their content fits in. After all, both scholarly and military writing are deeply entrenched in the “formal features” of genre that Devitt suggests we work within, but beyond.

Through understanding of and perhaps rebellion against these formal features, our students may best work to blend form and content to fit their audience. And, as Naval Postgraduate School Writing Coach Aby McConnell testifies, a basic formula for understanding the writing assignments they’re tasked with is helpful for our new student writers. Devitt agrees, stating, “If a writer has chosen to write a particular genre, then the writer has chosen a template, a situation and an appropriate reflection of that situation in sets of forms” (582).

As such, based on Devitt’s conception of genre, I offer the below model for our students.

The Heart of the (Subject) Matter

[E]ach person through genred communication learns more of his or her personal possibilities, develops communicative skills, and learns more of the world he or she is communicating with.

Charles Brazerman (17)

The content of academic writing, as shown in the above model, is where subject matter—and the students’ command over their subject matter—informs and creates scholarly writing as a genre.

As military scholars, our students are writing to an audience of experts and egos—two commonalities between the scholarly and military worlds. Whether graduate students or undergrads, our students come into their writing assignments with growing knowledge and expertise in their military and government fields; and their discourse communities take great pride in this expertise.

But the subject matter they must navigate in school will be new to them. Special Operations Forces officers, for instance, know how to apply unconventional methods in strategic warfare, but have they ever performed a regression analysis to examine the situational variables and arrive at the most statistically sound tactics? Surface warfare officers successfully operate intricate ship systems, but can they come up with code that allows them to train in virtual reality?

Understanding the subject matter, old and new, is even more important in an academic setting because our students are communicating their expertise (old and new) in a new genre, with values that differ from the writing genres of their professional military lives. As described in more detail in my last post, scholarly writing is argumentative and persuasive whereas much of our students’ writing in the military and government is taken for face value. When writing for an academic audience, our students must engage in what Timothy Crusius and Carolyn Channell call “mature reasoning”: they must make arguments that are well informed, self-critical and open to criticism from others, conscious of their audience, and cognizant of context (14).

Academic writing therefore values background information that frames and highlights a problem; it values review of literature, prior research, and evidence to support the importance of the problem and viable solutions. While military and government writing typically prioritizes a single perspective, scholarly writing values discussion of multiple perspectives and counterarguments that strengthen the author’s recommendations and address potential gaps.

By applying their growing knowledge and expertise of military and government subject matter (content) to this new academic writing template (form), however, our students can create meaning. What’s more: they can become more comfortable with their military and academic identities.

Genre and Identity

[U]nderstanding the group’s values, assumptions, and beliefs is enhanced by understanding the set of genres they use, their appropriate situations and formal traits, and what those genres mean to them.

Devitt (582)

Educator and scholar Charles Brazerman believes that “we develop and form identities through participation in systems of genres” (15). College students, he says, participate in these systems of genres as they write papers for their classes, and as they engage with their classmates, professors, and the life of the academy. As they do so, moving from class papers to theses and dissertation, students “reinterpret, hybridize, and improvise upon and within the forms of expression and contribution expected of them” (16, citing Prior).

But while genre feeds identity, identity also feeds genre. By writing in a certain genre, “You develop and become committed to the identity you are carving out within that domain,” Brazerman says (14). So by writing academic papers that address their growing expertise in military subject matter, our students are solidifying their identities as military members and as scholars.

However, they are also pushing the boundaries of their scholarly genres, as Devitt suggests, to respond to the needs of their subject matter. In this sense, “genre is a dynamic response to and construction of recurring situation, one that changes historically and in different social groups, that adapts and grows as the social context changes” (580). Our students’ writing, as I’ve ruminated previously, is an opportunity to harmonize the contact zone between military and academia.

Form and Content at the Writing Center

The question remains, however: How do we get our students there? How can our form + content model equal meaning for our students’ audiences, and how can we facilitate that meaning at the writing center?

Devitt believes that conversations about genre can be useful during the revision process. We can use genre to help our students see, for instance, if their intent matches their execution. As Devitt explains, “In revising, a writer may check the situation and forms of the evolving text against those of the chosen genre: where this is a mismatch, there is dissonance” (582).

Since most writing center work is revision work, genre-related questions for a student might include:

- What did you set out to prove?

- Does your thesis statement prove this point, or your eventual conclusion?

- Have you included this main point upfront, and provided audience-specific context?

- Where are the specific pieces of proof that you use to support your argument?

- Are those proofs presented in headings? In topic sentences?

- Does this paragraph contain evidence to support your claim?

- How do your sources support—or detract from—your claim?

- Is your evidence organized clearly and logically?

- What larger conversation are you joining, and have you addressed that conversation in your introduction and conclusion?

- Do your recommendations offer actionable solutions?

- Do your recommendations call back to the context in your introduction?

Here are some tools that may be helpful in examining form as it relates to content and subject matter:

- Clustering (see Dawson and Essid)

- Reverse outlining (see UNC Writing Center)

- Thesis statement refinement (see “Thesis Statements”)

- “Establishing why your claims matter” (Graff and Birkenstein 303)

- Mature reasoning checklist (Crusius and Channell 14)

- “Entertaining objections” (Graff and Birkenstein 82)

- Writer’s notebook (Crusius and Channell 17–19)

Works Cited

Bazerman, Charles. “Genre and Identity: Citizenship in the Age of the Internet and the Age of Global Capitalism.” The Rhetoric and Ideology of Genre: Strategies for Stability and Change, edited by Richard Coe et al., Hampton P, 2002, pp. 13–37.

Crusius, Timothy W., and Carolyn E. Channell. The Aims of Argument: A Brief Guide. 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Dawson, Melanie, and Joe Essid. “Prewriting: Clustering.” University of Richmond Writing Center, 2018, writing2.richmond.edu/writing/wweb/cluster.html.

Devitt, Amy J. “Generalizaing about Genre: New Conceptions of an Old Concept.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 44, no. 4, Dec. 1993, pp. 573–86.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say / I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. 3rd ed., W.W. Norton, 2017.

“Thesis Statements.” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Writing Center, writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020.

UNC Writing Center. “Reverse Outlining.” YouTube, 6 Sept. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZxphibAqb4&feature=youtu.be.

Sources Consulted: Academic Writing Formula Infographic

“Academic Writing.” Purdue Online Writing Lab, owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2020.

“Argument.” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Writing Center, writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/argument/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2020.

Crusius, Timothy W., and Carolyn E. Channell. The Aims of Argument: A Brief Guide. 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Devitt, Amy J. “Generalizaing about Genre: New Conceptions of an Old Concept.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 44, no. 4, Dec. 1993, pp. 573–86.

“Joining the Academic Conversation.” Naval Postgraduate School Graduate Writing Center, my.nps.edu/web/gwc/joining-the-academic-conversation. Accessed 8 Feb. 2020.

“What We Do.” The Green Belt Movement, www.greenbeltmovement.org/what-we-do. Accessed 8 Feb. 2020.

Maathai, Wangari. “An African Future: Beyond the Culture of Dependency.” Open Democracy, 27 Sept. 2011, www.opendemocracy.net/en/an-african-future-beyond-the-culture-of-dependency/.

The views expressed on this website are the author’s alone. They do not reflect the views of the Naval Postgraduate School.